Gropius House

Gropius House

Landscape

The Gropiuses believed that the relationship of a house to its landscape was of paramount importance, and they designed the grounds of their Lincoln house as carefully as the structure itself.

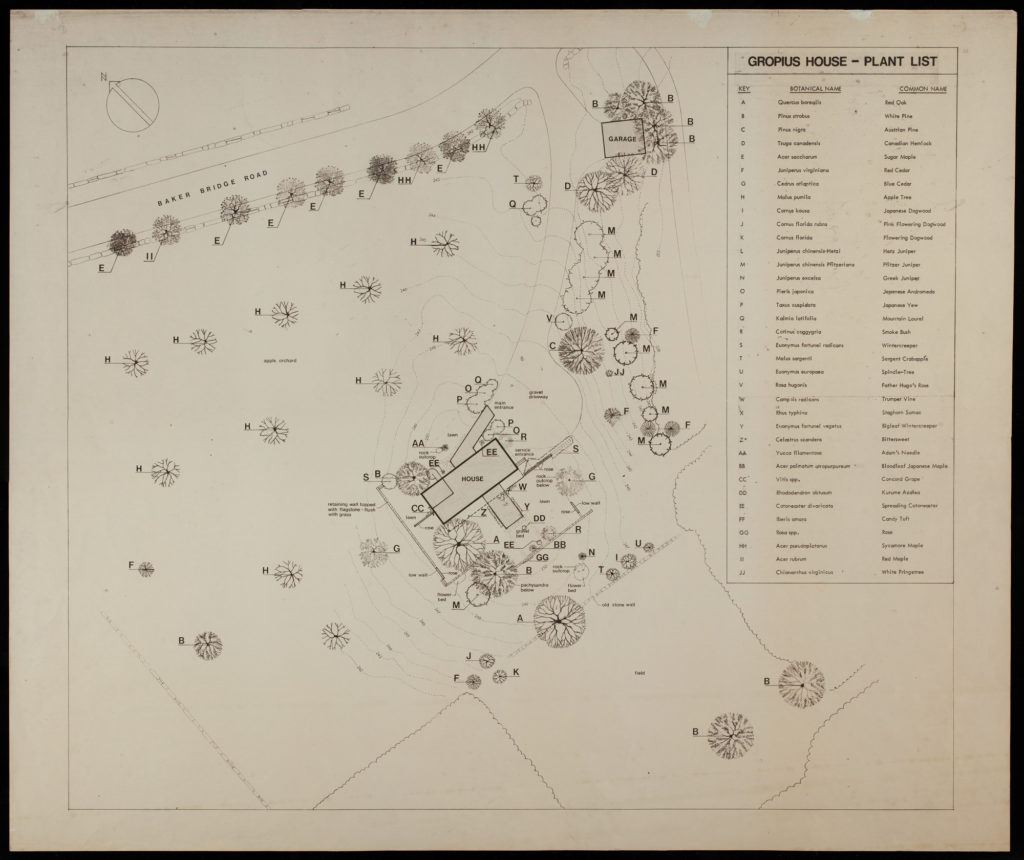

Plant Plan

Trees and shrubs were carefully selected by the Gropiuses when they planned the Lincoln house. They selected plant material that they knew would survive the harsh conditions of their windy hill, and for the most part, the trees and shrubs thrived. This plant plan shows the surviving plant material in the 1980s at the time the house came to Historic New England. Significant losses from the original plan include an American elm tree by the front door that died of Dutch Elm Disease and a beech tree in the center of the driveway that had outgrown its space and was transplanted to a building that Gropius was working on in Cambridge.

Landscaping the Lincoln House

Gropius sited the house atop a hill that overlooked Mrs. Storrow’s apple orchard to the north and west, and a long view to a meadow to the south and east. The intention was that the house’s large windows would look across an open landscape. As seen in this 1950s photograph, it was a house on a hill but anchored by large trees surrounding the house.

In the fall of 1937, before the house design was even completed, Gropius moved mature trees, most of which came from nearby woods, and planted them around the house site. The Gropiuses selected Scotch pine, white pine, elm, oak, and American beech. The earliest surviving photographs of the construction site show the frame of the house with mature, wrapped and wired trees already in place.

The house sat on a grassy plinth defined by stone retaining walls capped with flagstones for easy mowing. A “civilized area” around the house included a lawn extending roughly twenty feet around the house.

The Gropiuses took advantage of old farm walls that crisscrossed the property and helped define an even more wild area of the landscape. They “rescued” boulders that they found and created small gardens as focal points which they filled with perennials including iris, peonies, and phlox.

When the house was completed, the Gropiuses planted bittersweet, trumpet vine and Concord grape to connect the house with the landscape. A wooden trellis reaching from the east side of the house was covered with pink climbing roses and morning glory, and one on the west side supported a grape vine. Both theses trellises provided privacy and protection from the road.

A garden bed with the same dimensions of the screened porched continued the reach of the house into the landscape, with a “viewfinder” at the end framing a view down the hill to the meadow. Originally a garden with spring bulbs and perennials, the garden was the focus of Ise Gropius’s attention, as the maintenance of the garden beds were her passion. Her goal was maximum impact for minimal effort, yet she spent many hours each week planting, weeding, and trimming.

Around 1957, after a summer trip to Japan, Mrs. Gropius redesigned the perennial bed in imitation of a Japanese garden. She replaced the bulbs and flowering perennials with widely spaced azaleas, candytuft, and cotoneaster, covering the soil with a layer of gray gravel. A miniature Japanese maple was place in the center of viewfinder.

Beyond the well-tended ring around the house, the apple orchard and meadows were left to grow naturally. By mowing the orchard grass two or three times during the growing season and keeping the ever encroaching woodland under control, the Gropiuses maintained sweeping views to the east, south and west and preserved the feeling that the house stood high on a hill. As adjacent lots were sold, neighbors wanted more privacy and they allowed the woods to fill in along the Gropiuses border, resulting in a much less open appearance than the Gropiuses wanted.

In 1938 when the Lincoln house was built, the Storrow orchard was already mature. While she was alive, Helen Storrow had the apple trees sprayed and pruned, but after her death in 1945 the Gropiuses decided to let the tree grow naturally. Over the decades that followed, many of the apple trees became diseased and several died of old age. Historic New England is working now to bring the orchard back to its appearance in the 1960s.

One of the greatest pleasures derived from the landscape was the abundance of wildlife the Gropiuses saw on a daily bases. Ise Gropius filled and maintained more than one dozen bird feeders and bird houses on the property and claimed to have known more than ninety birds personally. She also invited the local family of raccoon (and their offspring) to the terrace for daily feedings.